Modeling a piano synthesizer

How I will create a physically-modeled piano synthesizer.

I play piano, and I love the instrument so much. One time, I was looking for piano VST plugins to complement my piano practice and performance. Upon observing the plugins I find, which are mostly samplers (synthesizers which play pre-recorded sounds), I stumbled upon Pianoteq which physically models a piano from the strings, to the acoustics of the soundboard. I was so amazed with how robust Pianoteq is with its vast array of customizations, that I took it as an inspiration to create my own synthesizer in order to better understand how the piano sounds are produced (even though I’m merely an enthusiast and not a piano builder myself). Mad props to the people at Modartt.

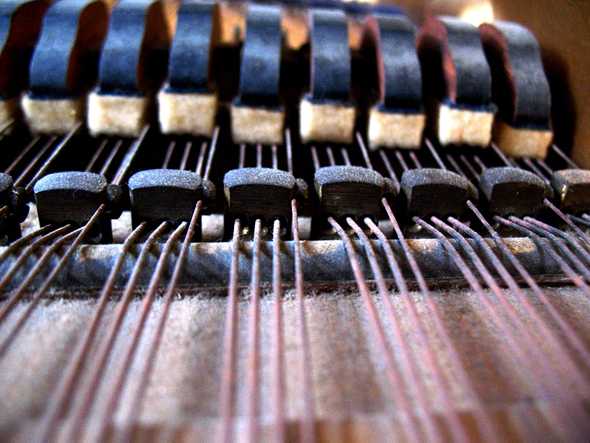

A piano has three fundamental strings laid out on most keys (excluding the aliquot strings found on some pianos such as Blüthner’s), although lower keys usually have less strings due to the fact that the sound produced upon striking the keys are louder and “muddier”—that is, a lot of overtones of these notes are not part of the harmonic series. This contributes to the keys’ metallic sound.

On which keys the number of strings start to decrease differs from each manufacturer—although in this top-down picture of a Steinway Model D, the last note which has three strings is a B♭1 (our reference note here is C4 - Middle C), then the number of strings do not decrease again until F1. From there to the lowest note A0, only a single string is reserved for each note.

For comparison, a Bösendorfer Grand Piano 200 has 3 strings until B2, then 2 strings until F♯1. Note that the Steinway is a concert grand, while the Bösendorfer is a shorter parlor grand, in which the latter could have required more strings to amplify the sounds because of its smaller soundboard.

From this construction, I have considered that “playing” a note constitutes to striking the strings, which then I shall proceed to physically model. The amount of strings to be modeled depends on the key as well as the size of the soundboard. We couldn’t interpolate the string count because it is a discrete value, so we should set constraints on string count with respect to the soundboard size—the longer the soundboard, the more a piano is preferred to have less strings.

But strings on a piano doesn’t sound on their own—they must be acted upon by something. Usually it is the row of hammers seen moving alongside when keys are pressed, but inside there are a lot of moving parts that constitute to the modern piano mechanisms. And pianos are not just played by keys, but the pedals are also used to create more expressive music. I shall delve on those mechanisms as soon as I start working on this project again.